In a LinkedIn post, Richard Millington shared a graphic comparing what brands want to what members want. He goes on to say that the trends in 2024 are making the delta between these goals wider. That’s already causing problems for brands and those problems won’t get fixed until companies grapple with the dilemma and make some hard changes. Chief among them: embracing community everywhere.

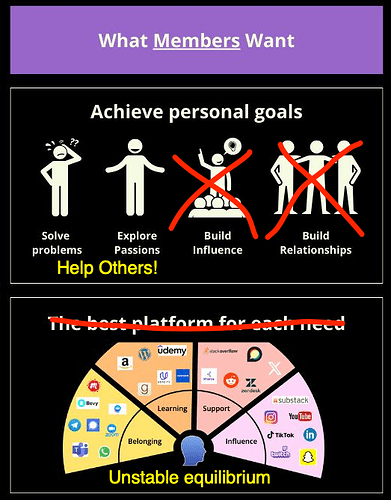

I respect Richard. He’s been very successful for longer than I have and clearly knows his stuff. But he is laser focused on brand communities and that makes his advice counter-productive for other types of communities. Based on my experiences as a community member and manager, I made a few edits to the “members want” side of the graphic:

What communities want

Communities have an implicit goal of helping other people, which has the pleasant side-effect of fulfilling the solve problems and explore passions goals. The result is a virtuous feedback as members gain a deeper understanding of the subject and use that knowledge to help others. Online communities have the double benefit of creating public artifacts as people help each other so that even people outside of the community might benefit.

Of course some people do want to build influence. For a brand, these people can be incredibly valuable. But for almost any other type of community, individuals building influence can be a distraction to the goals of the community itself. (I’m talking about the actual community goals rather than goals of the company that sponsors the community.) Self-promotion runs counter to the larger goals of the group and which is one reason it can be considered spammy. Influencers build artifacts to build their own reputation rather than help the group.

In the same way people who come in order to build relationships are creating something theoretically very good, but not particularly helpful to the goals of the group as a whole. Clay Shirky explained in “A Group is it’s Own Worst Enemy”:

So there’s this very complicated moment of a group coming together, where enough individuals, for whatever reason, sort of agree that something worthwhile is happening, and the decision they make at that moment is “This is good and must be protected.” And at that moment, even if it’s subconscious, you start getting group effects. And the effects that we’ve seen come up over and over and over again in online communities.

Unless the group is very specifically about forming relationships, this individual goal conflicts with the group’s goal. So whether you’d like to encourage it or not, the community isn’t going to be excited about people building influence or relationships instead of being helpful. When I’ve tried to integrate self-promotional goals into communities, inevitably it’s a fight the group wins.

Where we go on our vacations

For a change of pace, think about the last vacation you planned. Chances are good you either went to a place of:

- natural beauty or

- cultural importance.

Let’s set aside nature for a second and think about cultural destinations:

- Eiffel Tower

- Pyramids of Giza

- Taj Mahal

- Sydney Opera House

- Cristo Redentor

- Great Wall of China

- Statue of Liberty

What do you notice about these attractions?[1] Each is a monumental edifice created by human ingenuity and labor. Maybe you had less imposing attractions on your list: art, food, music, gardens, theater, transportation, etc. Not quite so impressive for Instagram, perhaps, but worthy attractions nonetheless. Then you have Los Angeles where people come to be vaguely in the place movie and television magic happens.

In other words, we visit cultural sites in order to see what people have made, not necessarily the people themselves.

Now think about what people say when they come back from vacations. Invariably you’ll here something like “The people there are just wonderful!” Why is that?

Once you’ve seen the sights, the novelty of the experience wears off. I used to take the bus from Westwood to Pasadena. I’d wait for my transfer on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just across the street from Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. While tourists from around the world gawked, took pictures with fake Spidermen and bought cheap souvenirs, I was just hoping to be left alone on my way to work. I wasn’t seeing the glitz and glamour anymore.

What sticks are interactions with specific people:

- The waiter who begged us to get cookies for dessert because they were better than you might expect. (They were!)

- The tour guide who clearly loves her city and wants to share it with everyone.

- The dour lady at the market whose face lit up when her young son showed off his coloring page.

These human interactions matter because we enjoy connecting with other people even in small ways. Paradoxically we need the cultural artifacts to bring us to places where our eyes are opened to ordinary interactions with other humans.

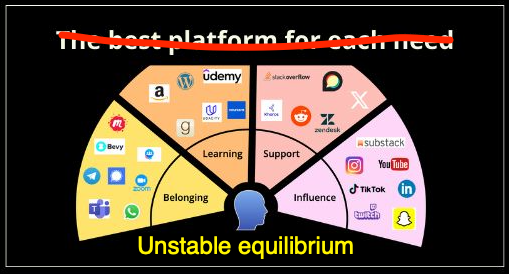

Every community is a local maxima

The platform section of Richard’s diagram confuses me. I don’t see any evidence that members think of community platforms at all unless their community is considering a change.[2] Discourse turns out to be a pretty useful learning platform. When it comes to feeling a sense of belonging, Twitch excels where Microsoft Teams doesn’t. Substack strikes me as a place where people who already have influence go to get paid rather than a place to build it in the first place.

Twitter wasn’t designed for support and is notably poor at that function. For some reason Twitter became particularly influential among company leaders. When they couldn’t get help through regular support channels, dissatisfied customers hit upon the idea of mentioning a company on Twitter. That way more people would see the problem. Companies that care about their image on Twitter will respond quickly, which is a sort of cheat code for getting help.[3]

While it does help a few individuals get their problems sorted out, Twitter for support wrecks havoc on a customer support team. At Stack Overflow, I put in time answering support emails. (You can read about it in a series of articles I wrote at the time.) We switched to Zendesk, which really is a platform suited for support, and immediately benefited from automatically delegating tickets to specialists and powerful macros for creating appropriate responses. Responding to customers on Twitter was a distraction and hurts the experience for people who go through the correct channel.[4]

Like going on vacation, people are attracted to online communities with impressive artifacts on display. People stick with groups because of the connections they form. It’s an unstable equilibrium. At any point people might choose to leave the group, which creates a negative feedback cycle. Farsighted community managers know the latest hotness is almost always temporary. Platforms that have survived technological and cultural disruptions in the past have better odds in the future.

Design putting greens, not driving ranges

While I’m critical about the “What Members Want” graphic, I agree with Richard’s assessment, in a different article, about what learners[5] want:

“Easier to find information”

“Stay informed about best practices / learn what others are doing”

“Avoid mistakes / find answers to problems”

For a community motivated by helping others, these concerns inform how members interact with the software. People instinctively think about how the artifacts they are creating will be viewed by anonymous strangers. Stack Overflow’s community notoriously criticizes people who ask questions without doing their homework because they optimize for pearls. When you land on a Stack Overflow question, you can be pretty sure the answers will be at least incrementally helpful, if not definitive.

So it was a bit of a shock to come back from sabbatical and discover the Stack Overflow homepage stopped showing a list of questions and became an ad for Stack Overflow products. The reason, of course, was that the company’s focus had shifted from helping developers learn to selling them services. Unfortunately the new page was a generic marketing page, i.e., crappy. It was a long shot that anyone would go from seeing that content to paying for one of the listed services.

Golfers have a saying:[6]

Drive for show.

Putt for dough.

It’s also a recipe for truly helpful internet resources. Instead of creating a big open space for everyone, the best landing page is a specific one that absolutely helps a smaller number of people. Like a golf green, it’s a smooth plateau with a clear goal. Ideally, surround that plateau with other, closely related landing pages. That gives your site a chance to answer the next question or curiousity without visitors rolling back to the Google fairway.

To the degree your community is motivated by helping others, consolidating on a single platform makes finding information a lot easier. This isn’t about the company seeking control, but rather about empowering the community to help others. Ultimately community managers aren’t tasked with finding an audience, but with guiding groups to fulfill their mission.

See also:

- https://24.199.105.5/t/dont-let-community-everywhere-distract-you/116

- https://24.199.105.5/t/expanding-community-organically/120

Other than the contributions of Gustave Eiffel to this list. ↩︎

And in that case, their current platform is “best” because they’ve adapted to the quirks. ↩︎

Full disclosure: my wife and I got help with our credit union after she posted a complaint on Facebook about them. ↩︎

Ideally the people who monitor Twitter and other social media would simply send a link to the official support channel and maybe offer to shepard the ticket through the system. ↩︎

The article also explains how this is a more useful term than “lurkers”. ↩︎

I’m not an expert, though I do play a round of disc golf from time to time. So I looked up the exact wording and learned the saying doesn’t apply. ↩︎